This coming 15 October, the State Administration Council, or the coup regime led by Min Aung Hlaing, is reportedly hosting the 8th anniversary ceremony to mark the signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA).

The document’s title is misleading in that it is not about observing all-around ceasefire per se throughout the country, as the word “nationwide” would connote, but about establishing a new political framework, importantly within the 2008 Constitution of, for and by the Tatmadaw, for resolving the country’s protracted armed conflicts.

The document acknowledged the political nature of the armed conflicts. Harn Yawnghwe, former facilitator of ceasefires/peace talks between President Thein Sein and Ethnic Armed Organization (EAO) leaders, and the European-Burma Office Executive Director, observes, “President Thein Sein accepted and approached the peace process as a crucial issue of resolving political differences at the dialogue table (defined as ‘Political Affairs’ within the military’s 2008 Constitution) while during the Aung San Suu Kyi leadership (2016-2021), the same process was allowed to be re-defined by the Bama military leadership as “a security issue”. This formulation serves the interests of the Tatmadaw in that it put the Commander-in-Chief – as opposed to the President who enjoy either popular mandate or the constitutional mandate – in the driver’s seat.”

However, it is worth pointing out, irrespective of who is driving the process, its scope in terms of substantive political issues did not include the slow-burning conflict in Rakhine, Western Myanmar coastal region, with the shifting alliances in Rakhine state, post-genocide. If ceasefire and peace nationwide are the ultimate objectives it makes absolutely no sense to intentionally exclude the conflicts – including the Rohingya’s struggle for recognition and acceptance as a self-identified ethnic group, of which the genocide is the gravest byproduct, as well as the historical and contemporaneous grievances of the state’s ethnic majority Rakhine.

The front cover of Myanmar Ministry of Defence’s official publication Current Affairs, Special Issue, V. 12, #6 (15 July 1960) A group of young Rohingya women holding bouquets of flowers, symbolizing their welcome for peace.

The first page of the official summary of the Vice Chief of Staff Army Brigadier General Aung Gyi, delivered at the surrender/peace ceremony of Rohingya armed resistance units, which took place on 4 July 1960.

Elsewhere I have at length discussed the Rohingya genocide as not “simply” about the one-sided persecution and destruction of the entire Rohingya population over the last 40 years. But rather it is, and has been, emphatically speaking, the culminating outcome of the triangular conflict among the three actors, namely the predominantly Muslim Rohingyas who make up the 1/3 of the region’s total population, the Buddhist Rakhine, the 2/3 majority in that region, and the central ethnic Bama-controlled central government.

My own late great-uncle, Major Ant Kywe, who was an official organizer of the “peace” or “Surrender Ceremony of the Rohingya armed units on 3 July 1960 would be turning in his grave that the Rohingya population to whose elders he issued official note of Thank you have come to be victims of the military’s slow genocide. [Under the Commander, Lt.-Colonel Ye Gaung he served as the Deputy Commander of All Rakhine Commands, based in Rakhine State’s capital Sittwe, the Union of Burma Ministry of Defence].

No single ceasefire or peace process has ever made any public mention of the continuing conflicts in Rakhine, let alone insisting on the need to put this triangular conflict on the agenda of any peace talks.

For their part, apparently holding their collective nose, the international media outlets – Financial Times, no less – Western governments, World Economic Forum and international thinktanks (for instance, the International Crisis Group), and INGOs including the Oslo Peace Research Initiative [whose director even shortlisted the genocidal military’s leader for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013] had all egged on Thein Sein as a soft-spoken “humble” military reformer as if he were the “enlightened general”, Fidel V. Ramos of Myanmar.

Former President of the Philippines Fidel V. Ramos (second from left), with the author Maung Zarni, and several American friends of a Free Burma, Washington, DC, 2001.

I knew ex-President Ramos personally who was instrumental in the ouster of the Washington-backed dictator Ferdinand Marcos, and Thein Sein was no Ramos. Not even close. He was appointed by the Burmese dictator Than Shwe to manage the military-controlled commercial opening of Myanmar, not to rock the military’s boat.

Ex-General Thein Sein, made President by the retiring Dictator Senior General Thein Sein in 2010, meeting with US President Obama at the White House, 2013. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

As a matter of fact, President Thein Sein, the ex-general, who presided over the signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), had reportedly – and blatantly, really – informed Antonio Guterres, then head of the United Nations High Commission of Refugees, that Myanmar Government had 2 plans in mind in dealing with what he (Thein Sein) called “Bengali” population of by Rakhine: 1) deport en masse Rohingyas by shipping them out to a third (presumably Muslim) country or 2) put in refugee camps (where they would be fenced in and deprived of any interactions, or meaningful livelihood opportunities as is typical of all refugee camps).

In Thein Sein’s words: “The solution to this problem is that they can be settled in refugee camps managed by UNHCR, and UNHCR provides for them. If there are countries that would accept them, they could be sent there.”

These planned initiatives are, in effect, plans for mass deportation and segregation of an entire population, whose ancestral root has been well-documented, and accepted even by the Ministry of Defence itself as late as 1960, are crimes against humanity under international law. Shockingly, the top UN official whose task it was to discharge the commission’s (refugee) Protection Mandate chose NOT to kick up any fuss about this outrageous statement of INTENT by a head of a UN member state to commit a grave crime against a protected group or population within and across national boundaries.

As to be expected, Myanmar military has since reneged on its official promise of peace and development for Rohingyas – and Rakhine state as a whole. Nearly thirty years on Rohingya armed resistance, however ineffectual and discredited, continued. To its credit, the Karen National Union, the country’s oldest resistance organization founded in 1947, has acknowledged the Rohingya group identity and their struggle for rights to exist as a group within the federal union of Burma or Myanmar. [See below the issue Number Four of the official bulletin of the KNU, dated April 1986, which printed on Pages 1 and 2 Rohingya press statement.]

To my profound dismay neither the civilian leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi nor Myanmar’s coup-making military nor the Ethnic Armed Organizations (save the KNU) acknowledge, let alone include in any political negotiations or discussions, about the needs, struggle and conditions of Rohingya people. It is the acts of persecution and destruction of the Rohingya, and loud denials of these crimes, NOT the international media organizations, or international – as opposed to Myanmar1 – human rights activists that “tarnish “image of Myanmar” around the world, with the (credible and well-documented) Rohingya genocide allegations.

One of Myanmar state mouthpieces, Kyay Mon ewspaper, carrying Aung San Suu Kyi’s address to the country, under the bold-based headlines of “Clashes with Terrorists and the Reinforced Seucrity Measures”, 26 August 2017.

Repeating Myanmar military’s narrative of fighting (Muslim) “terrorists, the then de facto head of state Aung San Suu Kyi, officially referred to as “Myanmar State Counsellor”, assuring the public that her government had upgraded and reinforced security arrangements to protect the residents of Rakhine state, on the day Myanmar military launched the genocidal campaign against the Rohingyas, under the label of “Security Clearance Operations”.2

These nearly 8-decade-long conflicts rage on and engulf the entire society of 50 million Myanmar people, the conflicts have entered their 8th decade, with devastating consequences, to belabour the obvious. In the Rohingya case alone, nearly 1 million people had run their survival run across the borders into Bangladesh, which opened its borders on humanitarian ground: from across the Bangladesh-Myanmar land borders, local Bangladeshi authorities, and people could see the billowing of smokes from burning villages, hear even artillery fire and witness helicopter gunships shooting civilian populations from the air, and hence the border opening.

The 8-year-old National Ceasefire Agreement was signed between the representatives of the central military of the Tatamadaw, the 2nd civilianized military government and its parliament, both led by ex-general and President Thein Sein, on one hand, and the anti-military armed organizations – ethnically organized and so named Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). They have been fighting for democracy, human rights and federalist – as opposed to unitary – Union of Myanmar.3

Some Basics in Understanding Myanmar Military and Its “Peace” Efforts

There are some fundamental issues that need to be clearly understood before going to the specifics of the ceasefire negotiations and peacebuilding, so-called, including the NCA.

Firstly, it is vital to unpack the word “civilianized” here. The original civilianized military government was instituted by General Ne Win and his deputies in January 1974, which usurped power in the coup of 2 March 1962, which ousted the elected government of Prime Minister U Nu, and decisively ended the country’s parliamentary democracy system adopted upon independence from Britain in 1948.

General Ne Win (right) with Zhou Enlai, the first Prime Minister of the People’s Republic of China, May 1964. (Photo: WikiCommons)

The word “civilianized” means, in effect, a Public Relations act of top generals swapping their military uniform with civilian attire and giving up military’s ranking titles (generals, brigadier generals, colonels, etc.) before assuming cabinet positions and playing parliamentarians. This act of “civilianization” is little more than an image make-over in order for these men to blend themselves with the rest of the civilian society. Certainly, the ex-generals rightly feel they do not really have political mandate – or legitimacy – to rule the population – because they come to power in unlawful seizure of state power. Myanmar military’s peace ceremonies and the military-sponsored multiparty elections have all ended in tears. For they have been farcical and cosmetic.

In terms of the restoration of peace and political stability, democratization of politics, federalization of the state, and creation of a constitutional blueprint acceptable to all stakeholders – different social classes and diverse ethnic populations in Myanmar, some fundamental and profound obstacle remain here: the civilianized military men have proven incapable of shaking off their neo-feudal and neo-totalitarian mindset. Worse still, there is this institutionalized sense of Entitlement to Rule, instilled in Myanmar military officers over the last half-century while serving in the various branches of the military organization where the mode of communications and mode of operations are 100% totalitarian.

In short, none of the generals – not even those who were held up as “democratic reformers” including the likes of President Thein Sein and his deputies – has proven fit for the new purpose: to lead Myanmar’s democratic transition successfully. Take a glance at the military’s record of reforms, constitution-making and peacebuilding in Myanmar.

The first military junta’s peace overture to the “insurgent groups” issued on 11 June 1963, 15 months after the coup of 1962. Forward Magazine, V. 1, issue 22.

It defies logic for any observer or student of Myanmar politics to expect men with totalitarian mindset4 so steep in the patron-client neo-feudal relations and so accustomed to issuing or following Command to the letters, to establish genuinely democratic and federalist institutions. These men and their mass-murderous military organization cannot move the country’s political culture in the direction befitting a new set of representative governmental institutions including the legislature, judiciary and executive. Nor can they build lasting peace.5

A word about what ASEAN now officially refers to as “the single largest military forces” is in order.

The Burmese nationalist military was, until the bloody coup of 2021, generally referred to as the Tatmadaw or the “royal” military, created by as Fascist Japan’s naval intelligence division as a local Burmese nationalist proxy against the Allies in the emerging strategic zone named as “Southeast Asia” with its headquarters in Kandy, Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka). Its rank swelled during the World War II as local lads joined the organization as its avowed aim was the liberation of their country from a century-long British colonial rule. After the Japanese surrender in May 1945, the victorious British high command significantly reduced its troops size, but retrained scores of formerly Fascist-trained Burmese military officers in UK and the then British-ruled Malaya (Malaysia and Singapore) as part of the West’s scheme to fight the emerging Communist movements in Southeast Asia.

Watch the historic videorecording here by the United States Information Agency about the visit of the official State Visit in September 1966, 4 years after the military’s 1st coup and the slaughter of several hundred peaceful anti-coup protesters on Rangoon University campus on 7 July 1962. Still, wssith a full-21 gun salute, the US President LBJ welcomed the “distinguished” General Ne Win and praised “Burma’s dedication to peace.”

Any analysis of Myanmar’s “peacebuilding”, ceasefire negotiations, and conflict resolution or transformation must be grounded in the accurate understanding of this institution, the Pavlovian mindset of its officer corps and its political and economic – as opposed to professional and defence – agendas. The soldiers-cum-politicians will continue to behave as if they were still in the totalitarian command structure. Incentivizing a bunch of military men, with their ill-gotten gains and brute force, whether in their green uniform or civilian attire, to enter into dialogue with democrats, federalists and civil society representatives, is a giant leap of faith, on the part of international policymakers and advisers. The latter can pepper such calls for dialogue with faddish buzz words such as “Myanmar-led” or “all-inclusive”. Reciting the policy mantra of the “Myanmar-led all-inclusive dialogue” is tantamount to trying to change the leopard’s spots.

It is, bluntly put, the road to nowhere.

Negotiations, Peace-building, and Reconciliation: A Close-up Personal View

Having been involved in different initiatives of reconciliation and negotiations since early 2000, as a Burmese student of politics over nearly 35 years, an activist and a Bama from an extended Bama nationalist and military family in the heartland of Bama, I draw on my close-up observations to dissect the discourses of “peacebuilding” “ceasefire negotiations” or “reconciliation”.

For the record, in hopes of creating an ideologically liberal pool of talents with Myanmar root, after the old Military Intelligence Service under General Khin Nyunt was dismantled by Senior General Than Shwe and Vice Senior General Maung Aung in the autumn of 2004, I had reached out to a number of well-known western-educated individuals frosm or with root in Myanmar, significantly, including Harn Yawnghwe, Dr Than Myint-U, Dr Nay Win Maung (deceased), Dr Khin Zaw Win (former political prisoner) and a few others and facilitated their ties with the Military Establishment in Naypyidaw. Many of them had gone on to play peace facilitator and adviser roles, official and unofficial, under ex-General and President Thein Sein’s leadership.

(From left to right) the 3rd ranking coup leader General Mya Tun Oo (then Colonel, Military Affairs & Security or military intelligence; Dr Win Naing; U Myint Swe, Acting President of the State Administrative Council or the coup regime (formerly Lt.General and Chief of Military Affairs & Security); and the author, then an open advocate for dialogue & reconciliation with Myanmar’s unpopular generals, Dagon Hall, Military Headquarters, Rangoon, November 2005.

In June 2006, staying in a military’s guest house not far from Rangoon International Airport for several days, I pointedly asked, in a one-on-one conversation, the then Colonel Mya Tun Oo,6 head of the counter-intelligence division, “can you share your ideas, and feedback with your superiors?” He said, “Ah, Not at all.” In my previous Track II meetings with the Burmese military officials, I had observed the neo-feudal nature of interactions between him and his superior Lt-General Myint Swe in several private meetings I had with them. He only spoke when spoken to, and even then, in Attention.

Our conversation took place after he told me his boss and chief of the military intelligence Lt-General Myint Swe was ordered by Senior General Than Shwe, the then head of the ruling junta, to immediately transfer his portfolio as Head of the Military Affairs Security, a highly influential post, to the new pick, Lt-General Ye Myint, during quarterly commanders’ meeting held in Naypyidaw, and to leave the meeting room and return to Rangoon immediately. The transfer order signified that Myint Swe7 was deemed inadequate for the task of running the MAS well. No employment reviews. No complaint processes. Just like that. But this is the typical decision-making behaviour in a totalitarian military institution, with deep Fascist root of the WWII.

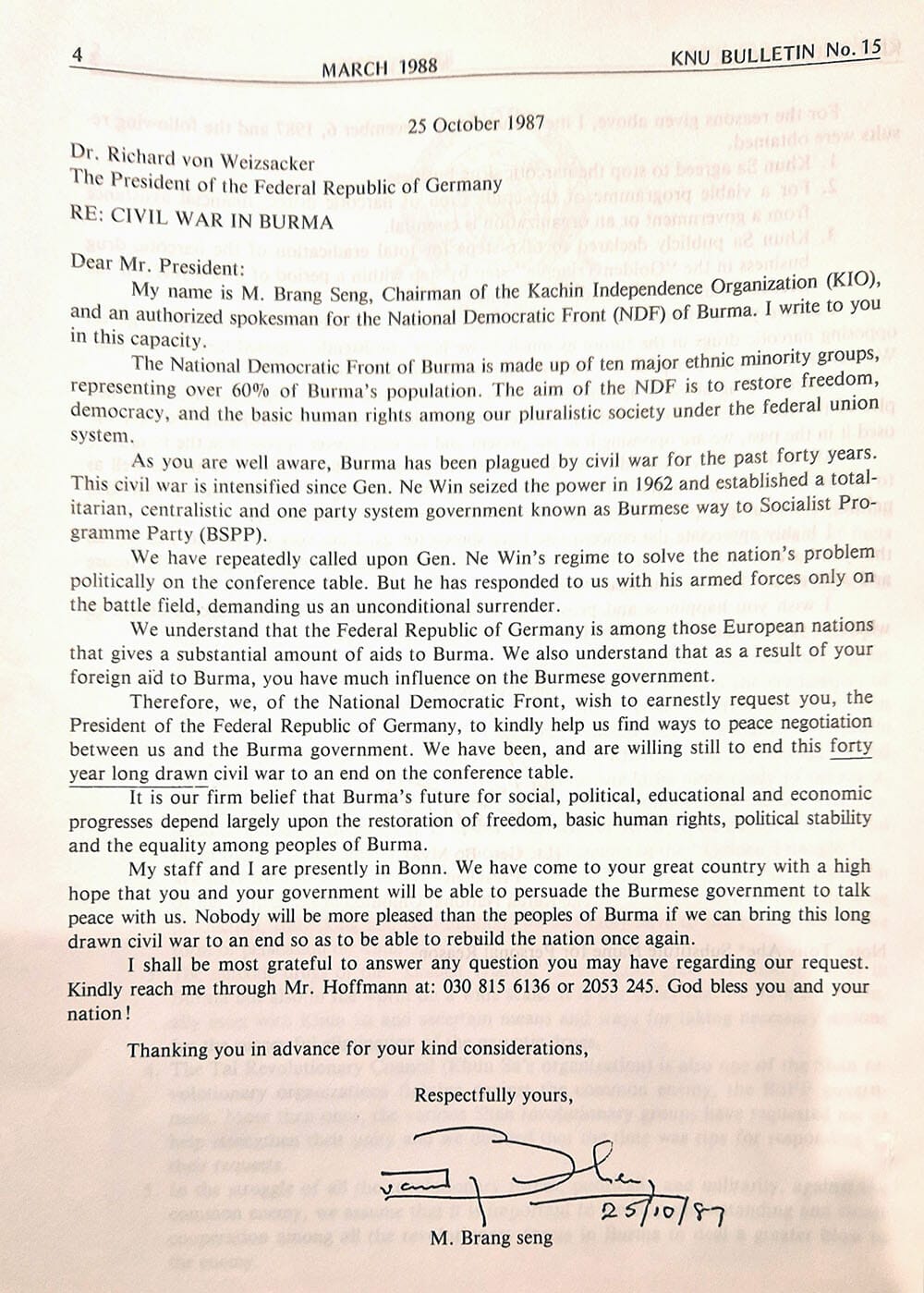

Rewind back to 1987, when today’s General Mya Tun Oo was a freshly commissioned Lieutenant out of the Defence Services Academy Intake – 25 (graduating class of 1984), the then Chair of the Kachin Independence Organization characterised one party military dictatorship thus: “(t)he civil war (has) intensified since General Ne Win seized power in 1962, and established a totalitarian, centralistic and one-party system of government….”

Totalitarian systems of (mal-)governance don’t change for the better over time. It is a cliché to say “the more things change the more they stay the same”.

Source: The Bulletin of the Karen National Union, #15, March 1988.

Secondly, this totalitarian and neo-feudal tradition of One Big General issuing orders after orders extends beyond the military’s internal domain of “hiring and firing” (or demotion, promoting or firing subordinates at whim). Its understanding is crucial to any analysis of ceasefire negotiations conducted by Myanmar military. In 2004, the then ruling junta which called itself the State Peace and Development Council, was hosting “peace talks” with the Karen National Union, which came about after the meeting between the late General Saw Bo Mya, then head of the Karen National Union and General Khin Nyunt, the 3rd ranking SPDC leader and chief of the Directorate of Defence Services Intelligence (DDSI or military intelligence).

According to Naw May Oo,8 whose partner and husband was a member of the KNU negotiation team, representatives from both sides – KNU and Myanmar military’s DDSI – had discussed and reached certain agreements on specific points in their peace negotiations, which were then only rejected by the then head of the junta, Senior General Than Shwe (retired) when the junta’s negotiators reported to the latter. Exasperated, the military negotiators would come back to the negotiation table the next day, asking to reopen the issues already agreed the day before.

A decade on, the civilianized general President Thein Sein, handpicked by the junta head Than Shwe to be the President of the military’s political party the Union Solidarity and Development Party, was able to persuade a total of 8 ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), out of the country’s two dozen EAOs (save the non-ethnic All Burma Students Democratic Front), to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). The signing ceremony took place on 15 October 2015 – in the presence of international audiences made up of representatives from neighbouring countries including Thailand, China and India, as well as diplomats from the European Union, UN and other international bodies.

Here it is worth noting that the first 5-years of what was then celebrated – in the international media and Myanmar policy circuses – as “Myanmar Spring” (2010-2015) appeared to have ushered in a new mode of operations within the civilianized military government headed by President Thein Sein. Suffice it to say, Myanmar military establishment was keen to speed up the Norway-assisted process of renormalizing its foreign relations with the West, particularly the Obama Administration, in its new strategic attempt to f move away from China’s tight embrace,9 secondly to attract international capital or foreign investment, and thirdly to augment its newfound acceptance at home with the so-called “performance legitimacy”.

A number of politically and militarily significant EAOs – such as the Kachin Independence Organization and the United Wa State Army chose not to sign the framework while the politically important Karen National Union (the country’s oldest resistance organization) and the Chin National Front or CNF became two key signatories. As a matter of fact, the 17-years-old bilateral ceasefire deal between the Kachins and Myanmar military had already broken down in early 2013 and the fighting had resumed between the two sides.

In my New York Times op-ed, several weeks before the signing ceremony of Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, I wrote that “the army is waging strikes (against certain EAOs) while the president is talking about peace does not reflect a split between the military and the executive branch; it is just the government’s version of playing good cop/bad cop.”

Nonetheless, the Obama Administration publicly lauded the NCA signing and his Myanmar counterpart, President Thein Sein for the ceasefire accord. Thein Sein declared that “(t)he nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) is a historic gift from us to our generations of the future. This is our heritage. The road to future peace in Myanmar is now open.”10

When Aung San Suu Kyi assumed the leadership after her NLD party defeated the military’s incumbent party – Union Solidarity and Development Party – two other additional signers, namely the New Mon State Party and Lahu Democratic Party, were later added to the list of signatories, bringing the total of NCA signatories to 10.

A well-known negotiator from an Ethnic Armed Organization who was deeply involved in the ceasefire negotiations from 2013 to 2015 reminded me several days ago that Aung San Suu Kyi was publicly urging the resistance organizations not to sign the civilianized military’s NCA. Instead, she wanted them to hold out until her NLD government came to power.11 The signing took place exactly 3 weeks before the scheduled 8 November 2015 general elections, which the NLD won in a land slide.

The opposition leader Suu Kyi chose not to attend the NCA signing ceremony in 2015. As the daughter of the martyred Aung San who was, rightly or wrongly, credited for the historic Pang Long Accord among several of the largest ethnic communities, who agreed to build a new post-colonial country as a federal union out of diverse ethnic nations, on the basis of group equality including the Bama majority. She saw peace-making and building national unity as her thing, not the military’s. But neither she nor the military has been able to build national unity. For they are all cut from the same ideological mindset according to which Bama are more equal among the rich tapestry of ethnic populations. And they suffer from the same self-inflicted wounds of Entitlement to rule.

With less than 10-years old baby of NCA, Thein Sein’s “road to peace”, under the same Min Aung Hlaing-led military that signed the NCA, turned out to be a dead-end. The supposed beneficiaries of Myanmar new generation have now become the backbone of the armed resistance, as its members – Generation Z – swapped their videogames for drones, bombs and machine guns to end what they have come to see as the intransigent and ruthless military whose troops have mowed down their peers in anti-coup protests which swept the country in the spring of 2021.

On the 2nd of October this year, commenting on the news reports about the military junta’s plan to hold a grand ceremony to mark the 8th anniversary of the NCA signing, Colonel Saw Kyaw Nyunt, an ethnic Karen, and spokesperson for the NCA signatories, told Thanlwin Times, “(w)e do not continue implementation of NCA at the moment. As you know, Political dialogues under NCA has stopped. As all relevant stakeholders no more took part in NCA, it has failed to meet requirements.”12

Min Aung Hlaing’s Coup killed both NCA and the Military’s Constitution

Since the widely unpopular coup of 2021, and the subsequent bloody crackdown of the anti-coup protest movement across Myanmar, not only the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement – formulated within the political framework of the 2008 Constitution – but also the Constitution itself is widely considered null and void.

To put it bluntly, both documents – the 2008 Constitution and the NCA – are dead in Myanmar’s public discourses as I have argued in my most recent analysis in the Democratic Voice of Burma on 5 October 2023.

For one thing, the majority Bama public overwhelming opposed, from the get-go, the military’s imposition of the Constitution on the country, especially since it enshrined lawful any future coups before they actually take place. Amidst the devasting Cyclone Nargis in May 2008, the then ruling junta – named State Peace and Development Council – rammed its Constitution of, for and by the military, in the hastily arranged Referendum while blocking the delivery of international emergency aid to the Nargis-effected Delta and coastal regions, with estimated 3-4 million cyclone victims.

The NLD had made repeated attempts to mobilize the public opinion for constitutional amendments, particularly to the clause that effectively bars the NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi from ever becoming de jure head of state or President on grounds of her British-born sons and the British husband (by then deceased).

Even if the public thought otherwise – that the NCA is a good thing that needs to be kept alive as a venue for ending Myanmar’s already protracted armed conflicts it would certainly feel surreal when some of the most important politicians in the country, including Aung San Suu Kyi and her NLD President Win Myint, are serving lengthy prison sentences on bogus charges of corruption and election frauds.

Equally important, two of the crucial EAO signers – Karen National Union and the Chin National Front – have already turned their back on the document and resumed full-blown resistance against what they saw as the Usurper, specifically Myanmar’s largest armed organization – the Tatmadaw – that staged the coup in February 2021, effectively having killed whatever transition or reform process there was, and along with it, hopes and aspirations of different ethnic communities and social classes.

Myanmar coup regime and its armed organization, the Tatmadaw, have been engulfed in multiple crises. In the last three United Nations General Assemblies in a row since 2021, Min Aung Hlaing’s State Administrative Council (SAC) has been denied Myanmar’s seat at the United Nations. For reneging its accord with the ASEAN to sue for inclusive peace dialogue, the SAC junta has also been barred from representing Myanmar at the highest levels of political meetings in the regional bloc ASEAN. It has been hit by multiple financial sanctions, by US, UK and the European Union.

The Resistance Organizations Are Building Autonomous Communal Structures, NOT Triggering State Collapse

The resistance movements have wrestled administrative control of local regions, with considerable success, in many a Myanmar region, including ethnic Bama heartlands, a traditional recruiting ground for the coup regime. The Rakhine State, the Karenni State, the Kachin state, and Chin state are reportedly most successful in this aspect of bottom-up autonomous state building by the resistance movements. To be sure, the exact number of the administrative units where local communities – as opposed the junta – have taken control of their own administration and welfare organizations is being contested.

The late Dr Chao Tzang Yawnghwe, Shan political exile and a former Commander of Shan State Army (1969-72), addressing the Free Burma Coalition Annual Conference, American Univetsity, Washington, DC, 2000.

The fact that communities of resistance against the formerly national armed forces – completely disowned even by the Bama majority public are building autonomous administrations from the bottom up is unprecedented in the country’s history, specifically in the ethnic majority areas.

Both the decades-old existence and the newly emerging administrative structures with welfarist state orientation during the post-2021 coup period, undermine effectively the well-worn argument that without the strong hand of the military, Myanmar’s ethnic centrifugal forces will create a pandemonium and the country with both vertical and horizontal conflicts will descend into a process of Balkanization, with cross-border implications in terms of the flow war-fleeing refugees into China, Thailand, India and Bangladesh 13

This is a glaringly self-serving but bogus argument that has been peddled by the Myanmar military propagandists and further promoted by state-centric experts and academics, in the international policy circles of diplomats, UN bureaucrats and think-tankers with their unhealthy fixation on “state actors”.

They are oblivious to the fact that it is the military-controlled state and its organs in Myanmar that are the prime driver behind the waves of forced migration, domestic political instability, chronic waves of violent revolts, and un-ceasing armed conflicts.

Of course, the non-Bama ethnic regions (such as Karen, Shan, Kachin, Karenni, and Rakhine) where a number of strong Ethnic Armed Organizations which enjoy the full support of local ethnic communities have years – for – of experience in building autonomous institutions.

The Karen National Union’s successful efforts at building alternative state structures – for lack of a better term – in the vast territories it controls and administers during its long-decades of resistance are well-documented and recently reported.14

The back cover of The Shan: Memoirs of a Shan Exile, (the Second Reprint, 2010, first published by the same publisher, ISEAS, in 1987)

In The Shan of Burma: Memoirs of a Shan Exile (published by The Institute of South East Asian Studies, 1987), my late friend, a fellow exile, and an early intellectual mentor of mine Chao Tzang Yawnghwe15 recorded his personal involvement in such local state building efforts as early as the late 1960’s. First, his background. Chao Tzang (better known as Eugene Thaike) was a son of the imprisoned Shan leader of the Federalist Movement, signatory to the (previously mentioned) Panglong Accord of 1947, and the 1st President of the Union of Burma. In his 20’s he abandoned his budding academic job as a tutor in English at the University of Rangoon, and joined the Shan resistance movement after General Ne Win’s coup in March 1962 which resulted in the forced displacement of his family, the death of his younger brother Mee Mee and the imprisonment of his father. A year later Eugene returned to Rangoon for peace talks when the coup regime – The Revolutionary Council – made a public and official peace overture dated 11 June 1963. When the peace talks collapsed, he returned to Shan State and became a leader in the Shan State Army, a national liberation movement fighting the Bama military which reneged on the promise of ethnic equality and federalist state building. In the Memoirs, Eugene wrote, “My tenure (1969-72), as commander of the 1st Military Region of the SSA was eventful. …” And he they went on to discuss what essential is a state building effort that he was initiating.

It is worth quoting Chao Tzang at length here:

Despite constant military pressures and the isolation of the SSA, I was nevertheless able to firm up the army and upgrade its performance – through organizational reforms and closer co-ordination of subordinate organs, such as military units, administrative (civil) network, and political teams. Most effective was the mobilization of local youths (aged 16-40) of both sexes in resistance work. They were organized into youth associations (one in each “village circle”) and given more voice in local and village affairs through self-help associations, parents-teachers associations, village government, religious communities, and village militia. The participation of the youths greatly facilitated bot only our war efforts, but improved the life of the people since it enabled us to set up a network of primary school and night schools, basic health care, and to improve roads, bridges, wells, sanitation, and personal security in the region.

The awakening and participation of local people in resistance work in turn helped me to curb latent dictatorial tendencies withing the (Shan State) army which were particularly serious in the accusations of spying for the enemy (Myanmar military).

He then discussed the instituting new procedures and orders to prevent summary executions and to administer fair criminal justice system within the local communities under his command.

Half-century after Chao Tzang’s experience of building a state ground up, with a welfarist and democratic orientation while at the same time waging an armed resistance against the ruthless and well-armed military in Rangoon the same pattern of work among resistance movements has become widespread.

Both NCA signers, for instance, the Chin National Front and the Karen National Union, and the non-signers such as the Kachin Independence Organization, Arakan Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Organization, the Kareni National Defence Force, and the Karenni National Progressive Party) are battling the SAC troops in various regions of the country. Whether it is portrayed as a civil war or a nationwide revolution is secondary to the fact that Myanmar military regime is extremely overstretched, is fighting its enemies in a multi-front war and losing it. Worst still, it has rendered the entire multi-ethnic society its enemies.

Conclusion: The Complexity and Proliferation of Myanmar’s Protracted Conflicts

Myanmar is known for its decades-long violent conflicts over political/ideological visions, organizational interests, the struggles for ethnic autonomy or federalist aspirations, and the majoritarian democracy.

The country’s complex and history of protracted conflicts – now in their 8th decade – need to be critically understood, if any domestic peace/ceasefire efforts are to bear fruit. Typically, these efforts are supported or aggravated by the policies and behaviour of the external actors, including various Western donors (in peace efforts), as well as the neighbouring China, India, Thailand, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

However, the complexity of Myanmar’s conflicts alone does not explain their protractedness. Neither should this factor of complexity as the conflicts’ central feature be used as an excuse for failing to find effective venues and strategies for negotiated settlements, as has often been cited by external actors with Myanmar concerns.

While the country’s largest armed organization – the Tatmadaw as the country’s armed forces is known – did not trigger the initial wave of armed revolts upon independence, its policies and institutional approaches to legitimate political grievances are most certainly responsible for the subsequent proliferation and prolongation of the armed conflicts, now over 20 ethnically armed organizations and estimated 600 anti-coup militias backed by some of the biggest EAOs such as the Karen National Union and Kachin Independence Organization.

Emphatically, there are two things that distinguish the successive military regimes from Ne Win to Min Aung Hlaing, from the last genuinely parliamentary democratic government of U Nu in so far as the protracted nature of these conflicts. First, the military’s approach to the existing conflicts has triggered the emergence of intra-minority or ethnic nationalities armed conflicts – or “horizontal conflicts” – over territories, commercial opportunities, trade routes/revenues and access to and control over lucrative natural resources. Second, the military rule and/or domination of national politics in Myanmar over the last 60-years is the most important contributor to the exponential rise in the number of non-Bama or Burmese ethnic communities that have established armed resistance organizations, with legitimate political objectives, namely varied aspirations for self-determination of respective ethnic groups.

To further elaborate, during the parliamentary democratic period (1948-1962), the number of ethnic armed organizations fighting for autonomy and self-determination was less than six, out of a few dozen politically important ethnic communities that form the country’s ethnic tapestry. Those who established their political organizations with armed wings – such as Rakhines, Mons and Karens – felt the pro-independence negotiations between the post-WWII Bama nationalists and Britain, and the resultant sovereignty transfer from London to Rangoon, excluded their voices and effectively marginalized their concerns and interests.

That said, the Nu government, established in accord with the political treaties with Britain, was, nonetheless, multiethnic and multi-faith in fact and outlook in orientation. Admittedly, the orientation of the newly independent state – the Union of Burma – remained a unitary, in fact, as opposed to genuinely federal as was envisaged by various ethnic group stakeholders such as Shan, Kachin, Chin, and even the dominant semi-enlightened Bama representatives. Still, U Nu government – and the state it was managing – had allowed for adequate political space wherein different ethnic groups aired their political differences and demanded their grievances, in particular, the lack of ethnic group equality, be addressed. The Shan led the above-ground Federalist movement while the Mon and the Rakhine pressed their demands for autonomy within the bicameral parliamentary proceedings.

But General Ne Win’s military coup of 1962 once and for all foreclosed this essential political space, equating as “attempts to break up” the transparent attempts at re-making the state in Myanmar into a functioning federalist democracy, which could satisfy various group aspirations.

This decisive closure of political space – wherein the needs and aspirations of diverse ethnic communities and social classes of Myanmar could be addressed peacefully and through public debates and parliamentary deliberations – has effectively set the stage for armed revolts. The ethnic communities and social classes rightly felt their grievances would not be addressed at all in the emerging neo-totalitarian military leadership which perceived differences in political visions and group interests as a threat to Myanmar’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

Instead, Ne Win and successive military leaderships to date have been hellbent on refashioning Myanmar’s state (organs) along their (military’s) sole neo-totalitarian vision of its One (Ethnic and Ideological) Voice, One Nation. In so doing, the military leaderships have been placing their institutional interests, as well as their personal political ambitions and economic interests above the rest of the society at large.

This, above anything else, explains why there has since 1962 been a proliferation of armed resistance organizations of varying intensity and effectiveness by different ethnic populations, with their divergent historical memories, linguistic traditions, political cultures, as well as the civilian bureaucracy. The latest military coup staged by Min Aung Hlaing on the bogus ground of NLD’s election frauds is unprecedented in that it triggered the predominantly Buddhist and Bama ethnic population – the country’s ethnic majority – to take up arms en masse through hundreds of localized militias – known as People’s Defence Forces.

In the ensuing 6-decades the military has equated its own organizational interests with those of both the state, as such, in Myanmar and of the country as a whole. Since Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council government (1962-1974), which remade itself as Burma Socialist Programme Party government (1974-1988), the successive generations of officer corps have been instilled with this perception that they and their armed organization alone, ultimately, represent the state – and their preferences in policies reflect “People’s Desire”.

Today, Ne Win and his failed BSPP military dictatorship are no more. It is this self-perception of the military as the only national organization capable of discharging its state- and nation-building duties that has, however, continued to shape the policies, behaviours and outlook of individual military leaders and their regimes they lead. But insofar as the Myanmar’s ethnic majoritarian society, they no longer see the once instrument of national liberation against the British rule as their national defence force. The bond between the ethnic nation of Burmese is as dead as the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement – and the military’s Constitution of 2008.

Maung Zarni

- In the decade leading up to the largest wave of genocidal campaign against Rohingya, virtually all Myanmar human rights campaigners and local NGOs and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs), as well as political parties including Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD, openly stood with the military.

- See my commentary on Aung San Suu Kyi’s role in the genocide. The real crimes of Myanmar’s Suu Kyi and the farce of her trial, Anadolu News Agency, 28 May 2021 at https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/opinion-the-real-crimes-of-myanmars-suu-kyi-and-the-farce-of-her-trial/2257077

- Myanmar signs ceasefire with eight armed groups | Reuters 15 October 2015.

- See my 3-part analysis of Myanmar military, originally published in Asia Times, October 2013: Part 1: Evolution of a mafia state in Myanmar | Zarni’s Blog (maungzarni.net) ; Part 2: Fascist roots, rewritten histories | Zarni’s Blog (maungzarni.net) ; and Part 3: A class above, the heaven-born | Zarni’s Blog (maungzarni.net)

- See my analysis of what is wrong with peace building initiatives in Myanmar with the military as the main driver. What is wrong with Norway’s Myanmar Peace Support Initiatives (MPSI)”, an official Oslo-commissioned critique by Dr. Maung Zarni | Zarni’s Blog/

- Mya Tsun Oo is part of Min Aung Hlaing’s 2021 coup regime, holding Defence Minister post, until the latest reshuffle in September 2021. He was my age peer, and for a number of years served as a liaison officer between myself and his superiors including Lt-General Myint Swe and the latter’s replacement Lt-General Ye Myint.

- A close relative of retired dictator Than Shwe’s wife Daw Kyaing Kyaing, Myint Swe was the military’s pick to serve as Vice President in Aung San Suu Kyi’s 1st elected government in 2016. He was made Acting President by Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing as the latter removed and imprisoned President Win Myint, for having refused to sign off on the coup on 1 February 2021 against the re-elected Aung San Suu Kyi government.

- Personal communications with Naw May Oo, 2004.

- To the displeasure of Beijing, and amidst the anti-China public sentiments in Myanmar, President Thein Sein unilaterally suspended the mega dam project on the origin, in Kachin state, of the country’s main river Irrawaddy. Ironically, while Thein Sein sought acceptance by Washington and attempted to keep China at bay, it was Aung San Suu Kyi who decided to prioritize her relationship with China’s top leadership, in a move clearly designed to rally Beijing’s support for her political party, something China had responded positively.

- Myanmar signs ceasefire with eight armed groups | Reuters 15 October 2015.

- Personal communication, 30 September 2023.

- https://thanlwintimes.com/2023/10/02/we-do-not-continue-implementation-of-nca-at-the-moment-political-dialogue-under-nca-has-stopped-colonel-saw-kyaw-nyunt-spokesperson-of-ceasefire/?amp=1

- On the subject of the coup military junta as the stabilizing strong hand of Myanmar see the Washington Post Editorial here https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/new-massacres-by-myanmars-military-demand-a-tougher-us-response/2021/03/29/d0eaa31a-90ae-11eb-bb49-5cb2a95f4cec_story.html

- Where The Revolution Is Working In Myanmar | MENAFN.COM 30 September 2023.

- In the early 1990’s we were both working on our PhDs – him on the comparative study of Burmese and Indonesian militaries at the University of British Columbia in Canada and I on the politics of education under General Ne Win’s military dictatorship in Burma, at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. He was both an intellectually and personally nurturing type of intellectual and a leader. After having survived an assassination attempt in the Northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, Eugene and family relocated to Canada, and he resumed his education at UBC. A political exile, Dr Chao Tzang Yawnghwe died of brain cancer in Vancouver in July 2004, after having contributed to the Burmese opposition movement for years.